The BBC has a nice documentary on Crossrail, a £15 billion project to build a new 120-km train line passing through central London. I knew that this is a great engineering challenge, but I did not appreciate the scale of difficulty the engineers faced. You can watch the three one-hour episodes here (need UK access), or here’s the summary of the interesting points illustrated with pictures (credit: BBC, Wikipedia):

1. The project is using eight specially made tunnel-boring machines (shown below), each with a female name, such as Elizabeth, Mary and Victoria.

2. One of the biggest challenges has been tunnelling under Tottenham Court Road station. It is where the tunnel-boring machine needed to pass through very crowded space. The tunnellers have labelled it “the eye of the needle”. There the 900-tonne tunnel-boring machine has had to pass through a space where 30cm above it was a live escalator and 85 cm underneath was the active Northern Line.

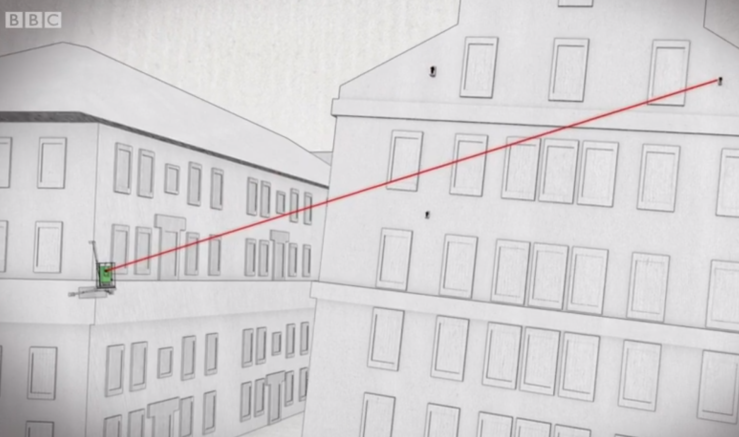

3. When drilling under London, tunnellers need to ensure that all the buildings above ground remain as they were. This is tricky because during the operation, there is every possibility of disturbing the earth beneath some ancient buildings, causing them to tilt or, worse, crash down. To monitor the balance, they have installed laser sensors which measure any movement. When the building starts sinking, the alarms ring.

4. The building then needs to be brought back to its previous stable state, which is done by injecting grout just at the right place to fill up any spaces that are causing the sinking. To do that, they have created 22 massive shafts throughout London, which have small pipes originating from them spreading through the ground beneath as a spider web. Whenever there is a disturbance that the laser monitors spot, they insert a tube through the right pipe that goes under the building and pumps grout in that area, which we are assured stops the building from sinking. Some shafts operators spend 16 hours a day doing this.

5. The Thames river is the first river in the world to have a tunnel built underneath it. That first 400m tunnel, opened in 1843, needed 16 years of work to build. The design of the boring machine built then by Marc Isambard Brunel is still in use. In the modern version the actual digging work is done by robotic arms rather than people. The tunnel under the Thames near Woolwich of about the same length as the 1843 one took only 8 months.

6. Despite nearly two centuries of expertise boring under the tunnel, it’s still quite a challenge. One of those difficulties is a tunnel near the Custom House station. Where they had to block the river, drain the area and work on expanding an already existing tunnel to fit the wide Crossrail trains.

7. When tunnellers use the word “breakthrough” they are literally breaking through something. And when they use the phrase “seeing the light at the end of the tunnel”, they actually see light at the end of the tunnel.

8. The Crossrail’s Canary Wharf station (shown below) is going to cost £500 million. Similarly, the new Farringdon station’s cost is £440 million.

9. Station constructions have 22-week period allowed for archaeological investigation, if an opportunity shows up. In an old city, it almost always does. Shown here is the remain of someone who died from bubonic plague, or Black Death, in the 14th century. More than 20 other such bodies were found in the same spot near Farringdon station.

10. Underground trains form an almost perfect air seal, pushing all the air in front of it at the same speed as it travels. Each underground station has to build ventilation systems to accommodate the pressure such pushed air can create. So next time you see a ventilation shaft outside a station, remember that is built not built to keep you cool underground but to make sure the air pressure created by trains doesn’t break things.