Bacterial diseases cause millions of deaths every year. Most of these bacteria were benign at some point in their evolutionary past, and we don’t always understand what turned them into disease-causing pathogens. In a new study, researchers have tracked down when this switch happened in a flesh-eating bacteria. They think the knowledge might help predict future epidemics.

The flesh-eating culprit in question is called GAS, or Group A β-hemolytic streptococcus, a highly infective bacteria. Apart from causing flesh-eating disease, GAS is also responsible for a range of less harmful infections. It affects more than 600m people every year, and causes an estimated 500,000 deaths.

These bacteria appeared to have affected humans since the 1980s. Scientists think that GAS must have evolved from a less harmful streptococcus strain. The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reconstructs that evolutionary history.

James Musser of the Methodist Hospital Research Institute and lead researcher of the study said, “This is the first time we have been able to pull back the curtain to reveal the mysterious processes that gives rise to a virulent pathogen.”

Genetic gymnastics

Musser’s work required analysis of the bacterial genetic data from across the world – a total of about 3,600 streptococcus strains were collected and their genomes recorded. It revealed that a series of distinct genetic events turned this bacteria rogue.

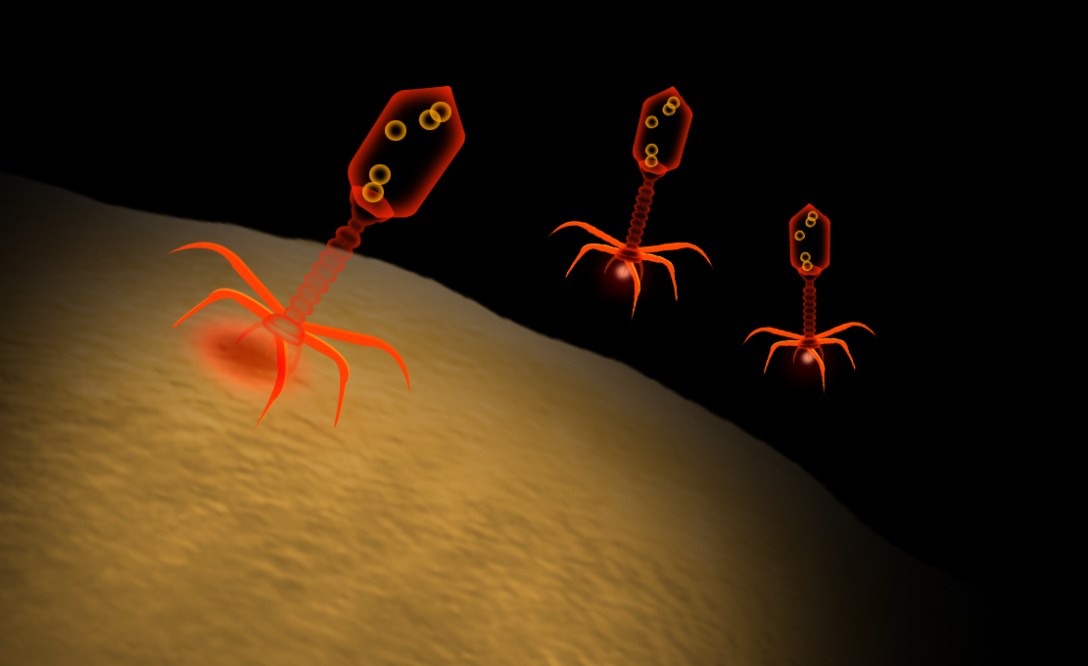

First, foreign DNA moved into the original harmless streptococcus by horizontal gene transfer – a phenomenon that is common among bacteria. Such DNA is often provided by bacteriophages, viruses that specifically target bacteria. Picking up foreign genes can be useful because it can improve the bacteria’s survival.

In this case, the foreign DNA that was incorporated in the host’s genome allowed the streptococcus cell to produce two harmful toxins. A further mutation to one of these toxin genes made it even more virulent.

According to Musser, another horizontal gene transfer event made a good disease-causing pathogen into a very good one. The additional set of genes allowed it to produce proteins that suppress the immune system of those infected, making the infection worse.

Marco Oggioni of the University of Leicester said, “Because this study used data of the entire genome, all the genetic change could be observed. This makes it possible to identify molecular events responsible for virulence, as you get the full picture.”

Musser could also accurately date the genetic changes in GAS by using statistical models to, as it were, turn back the clock on evolution. They say the last genetic change, which made GAS a highly virulent bacteria, must have occurred in 1983.

Continental drift

That timing makes a lot of sense. “The date we deduced coincided with numerous mentions of streptococcus epidemics in the literature,” Musser said. Since 1983, there have been several outbreaks of streptococcus infections across the world. For example, in the UK, streptococcus infections increased in number and severity between 1983 and 1985.

It is the same story for many other countries, with Sweden, Norway, Canada and Australia falling victim to what is now an inter-continental epidemic. The symptoms ranged from pharyngitis to the flesh-eating disease, necrotizing fasciitis.

“In the short term, this discovery will help us determine the pattern of genetic change within a bacteria, and may help us work out how often bacterial vaccines need to be updated,” Musser said. “In the long term, this technique may have an important predictive application – we may be able to nip epidemics in the bud before they even start.”

What Musser is suggesting is that if enough bacterial genomes are regularly recorded and monitored, there is a chance that mutations or gene transfers, such as those GAS experienced, could be found ahead of time.

But Oggioni is sceptical. “While making such predictions may not be possible, this research will have other applications,” he said. “Knowing which genetic changes happen when can help tailor drug discovery research in a certain direction.”

Oggioni added that Musser’s work with GAS is only a model. Using Musser’s methods to record the evolutionary histories of other pathogens could be quite useful to tackle the diseases they cause now and, perhaps, even those that they may cause in the future.![]()

Written with Declan Perry. First published on The Conversation. Image credit: Zappys Technology