The other day a lab-mate who started his PhD work with me made a neat observation. He said:

I find myself quite pleased to see how efficient I’ve become in the lab. While teaching the new student who started last week I realised that what takes them an hour and half to do, I can finish in under 20 minutes. Don’t get me wrong. I am saying this not to question the ability of the new student. Instead, I realise that having learnt the process so well, I plan my task around the rate-determining step in the process and thus, end up doing the whole task so much faster.

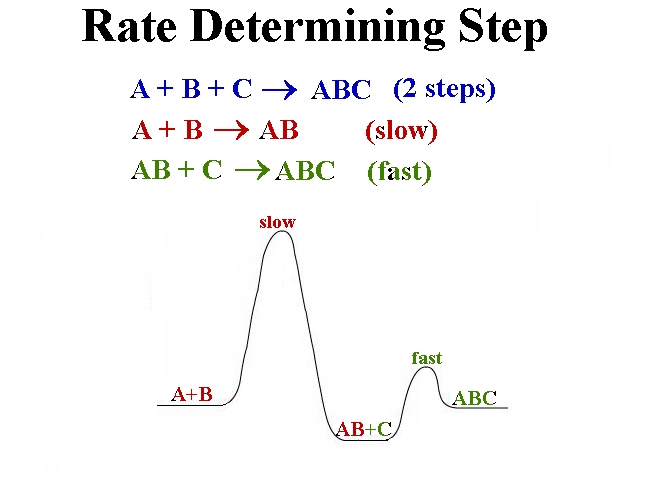

It’s an astute observation. I am writing this today because I think that this chemistry concept of ‘finding the rate-determining step‘ (aka the slowest step) can be applied beyond the lab to help improve our daily productivity. Let me explain through a trivial example.

On week days I have my lunch at the college hall. It can take me anything between 25 to 55 minutes to leave the lab, finish lunch and come back. The process can be broken down as below:

- 3-5 minutes: Ride to the college from the lab

- 5-20 minutes: Wait in queue to get the meal

- 15-25 minutes: Eat the meal

- 3-5 minutes: Ride back to the lab from college

If I now want to make the process productive, I need to find where can I cut down the extra minutes. The slowest step here is ‘eating the meal’ but I am going to skip optimising that because I’d like to enjoy the meal. Also, I don’t want to suffer an accident so I am going to skip optimising my cycling speed to cut down the riding time. That leaves me with ‘waiting in the queue’. I’ve observed that if I reach the college at 12.25 pm then I am usually amongst the first few students in the queue and end up getting served as soon as the hall opens at 12.30 pm. So if I make it in time then I cut my time in queue from 20 minutes to 5 minutes. I’d call this the rate-determining speed in the process and ensure that I reach at 12.25 pm. And I do just that, as Chris our head porter says, “First in the queue again, eh?”

Of course, that is a trivial example. But finding more important situations which parallel the example I gave would not be hard. Take the writing process for example. The longest step in the process turns out to be the editing. I find that if I keep on editing as I write then it takes much longer than editing at the end of finishing the first draft.

Of course, that is a trivial example. But finding more important situations which parallel the example I gave would not be hard. Take the writing process for example. The longest step in the process turns out to be the editing. I find that if I keep on editing as I write then it takes much longer than editing at the end of finishing the first draft.

While writing about this post I also realised that I’ve been applying the ‘finding the rate-determining step’ process without actually having thought about it that way. Hopefully, this post on wards I’ll think about it in a more-structured manner.