More than nine in ten cancer-related deaths occur because of metastasis, the spread of cancer cells from a primary tumour to other parts of the body. While primary tumours can often be treated with radiation or surgery, the spread of cancer throughout the body limits treatment options. This, however, can change if work done by Michael King and his colleagues at Cornell University, delivers on its promises, because he has developed a way of hunting and killing metastatic cancer cells.

When diagnosed with cancer, the best news can be that the tumour is small and restricted to one area. Many treatments, including non-selective ones such as radiation therapy, can be used to get rid of such tumours. But if a tumour remains untreated for too long, it starts to spread. It may do so by invading nearby, healthy tissue or by entering the bloodstream. At that point, a doctor’s job becomes much more difficult.

Cancer is the unrestricted growth of normal cells, which occurs because mutations in normal cell cause it to bypass a key mechanism called apoptosis (or programmed cell death) that the body uses to clear old cells. However, since the 1990s, researchers have been studying a protein called TRAIL, which on binding to the cell can reactivate apoptosis. But so far, using TRAIL as a treatment of metastatic cancer hasn’t worked, because cancer cells suppress TRAIL receptors.

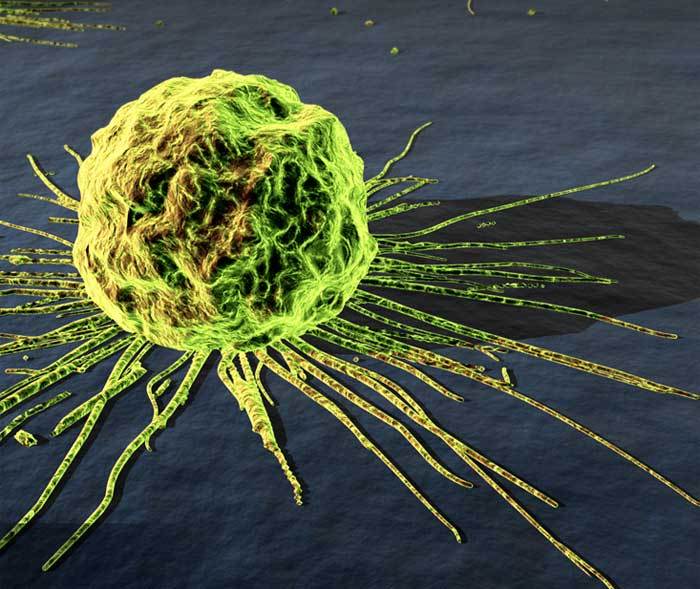

When attempting to develop a treatment for metastases, King faced two problems: targeting moving cancer cells and ensuring cell death could be activated once they were located. To handle both issues, he built fat-based nanoparticles that were one thousand times smaller than a human hair and attached two proteins to them. One is E-selectin, which selectively binds to white blood cells, and the other is TRAIL.

He chose to stick the nanoparticles to white blood cells because it would keep the body from excreting them easily. This means the nanoparticles, made from fat molecules, remain in the blood longer, and thus have a greater chance of bumping into freely moving cancer cells.

There is an added advantage. Red blood cells tend to travel in the centre of a blood vessel and white blood cells stick to the edges. This is because red blood cells are lower density and can be easily deformed to slide around obstacles. Cancer cells Have a similar density to white blood cells and remain close to the walls, too. As a result, these nanoparticles are more likely to bump into cancer cells and bind their TRAIL receptors.

King, with help from Chris Schaffer, also at Cornell University, tested these nanoparticles in mice. They first injected healthy mice with cancer cells, and then after a 30-minute delay injected the nanoparticles. These treated mice developed far fewer cancers, compared to a control group that did not receive the nanoparticles.

“Previous attempts have not succeeded, probably because they couldn’t get the response that was needed to reactivate apoptosis. With multiple TRAIL molecules attached on the nanoparticle, we are able to achieve this,” Schaffer said. The work has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

While these are exciting results, the research is at an early stage. Schaffer said that the next step would be to test mice that already have a primary tumour.

“While this is an exciting and novel strategy,” according to Sue Eccles, professor of experimental cancer therapeutics at London’s Institute of Cancer Research, “it would be important to show that cancer cells already resident in distant organs (the usual clinical reality) could be accessed and destroyed by this approach. Preventing cancer cells from getting out of the blood in the first place may only have limited clinical utility.”

But there is hope for cancers that spend a lot of time in blood circulation, such as blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes cancers. As Schaffer said, any attempt to control spreading of cancer is bound to help. It remains one of the most exciting areas of research and future cancer treatment.![]()

First published at The Conversation.

Image credit: Cornell University