Swine Flu is back, and it is spreading with a vengeance. The total number of recorded cases in India has crossed the 20,000-mark and it has led to more than 1,000 deaths. While this number is much smaller than the number of those killed by the 2009 swine flu pandemic, it is worrying because the new strain appears to be harder to treat. According to Om Jaslok, director of the infectious diseases department at Jaslok Hospital in Mumbai, patients need to be treated with anti-viral medicine oseltamivir for an average of 10 days, which is twice the length of treatment in previous outbreaks.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) had warned of such a swine flu outbreak as far back as 2013. The phenomenon of pathogens developing resistance to drugs is not new. Those few pathogens that survive the onslaught of drugs pass on their traits to the next generation, giving birth to a drug-resistant strain. What is worrying is that drug resistance is increasing at a much faster rate than the pace at which humans can come up with new drugs or treatments.

Disaster-in-waiting

While flu epidemics come and go, drug resistance in persistent diseases is even more worrying. Take the example of malaria, the biggest single killer of humans since our species began walking on this planet. In the last century, the increased attention to malaria produced drugs that could effectively treat the disease. One such drug is chloroquine, which was widely used across the world and saved millions of lives. However, since the 90s, chloroquine is no longer a weapon in the medical arsenal. Mosquito parasites—responsible for causing and spreading malaria—have become resistant to the drug, and we have been forced to develop newer drugs.

A bigger worry is the development of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics, first discovered in the early 20th century, turned lethal diseases, such as pneumonia, into treatable conditions. These drugs have become the bedrock of effective modern medical treatments. They are used in surgeries to protect patients from acquiring diseases via open wounds, and given to cancer patients to help boost their immunity against pathogens. But fewer of them are as effective today.

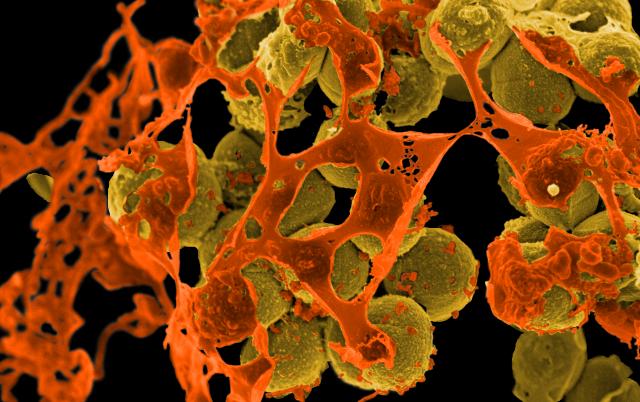

These antibiotic-resistant microbes are referred to as superbugs, and they kill ruthlessly. According to a report in the respected journal The Lancet, more than 58,000 newborns in India were killed in 2013 because of these superbugs, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile. One particular enzyme, New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1 (NDM-1), which helps create superbugs has been named after where it is believed to have originated, and we currently have no way of countering the enzyme’s spread.

You can act

The economic cost of drug resistance is potentially huge. According to the 2014 Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, the accumulated loss to global output by 2050 can be as much as $100 trillion, which is more than 50 times the current GDP of India. Even such a dramatic prediction may be an underestimate, according to Jeremy Farrar, the director of Wellcome Trust, one of the world’s biggest biomedical charities, because the review only includes direct costs. For instance, if routine surgeries become impossible because of antibiotic-resistant bugs, they will have an effect on healthcare as a whole and lead to more deaths.

There are ways in which we can fight against drugs resistance. One way is to invest more in finding new and more effective drugs. But success down this route has become much harder to achieve. The pharmaceutical industry is undergoing a crisis, producing fewer new drugs. The other way is to slow down the march of drug-resistant microbes. This requires that governments, doctors and citizens to work together.

Farrar notes that we have been taking antibiotics for granted, treating them as consumer goods. They seem to be “ours to demand from doctors and ours to take or stop taking as we see fit.” This is a huge problem. People stop taking pills as soon as they feel well, but that doesn’t mean the microbes have been completely eliminated. Instead the partial course of antibiotics leaves a great number of mildly resistant microbes alive, which then spawn new generations and spread drug resistance.

If we are not to return our healthcare back to the 19th century, where infectious diseases killed rampantly, we must learn to respect these wonder drugs. Doctors must be conservative in giving out prescriptions. And, if there is no option, the least patients can do is take the full course prescribed.

First published in Lokmat Times. Image by NIAID.