Researchers in the US have overcome a key barrier to making nuclear fusion reactors a reality. In results published in Nature, scientists have shown that they can now produce more energy from fusion reactions than they put into nuclear fuel for an experiment. The use of fusion as a source of energy remains a long way off, but the latest development is an important step towards that goal.

Nuclear fusion is the process that powers the sun and billions of other stars in the universe. If mastered, it could provide an unlimited source of clean energy because the raw materials are plentiful and the operation produces no carbon emissions.

During the fusion process, smaller atoms fuse into larger ones releasing huge amounts of energy. To achieve this on Earth, scientists have to create conditions similar to those at the centre of the sun, which involves creating very high pressures and temperatures.

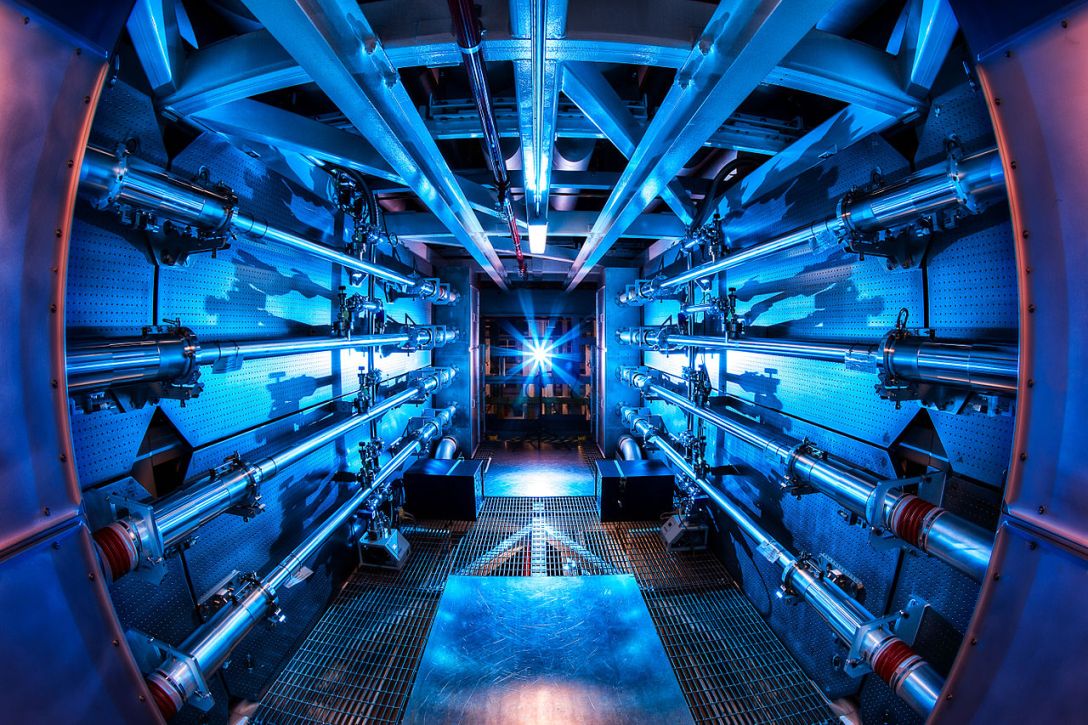

There are two ways to achieve this: one uses lasers and is called inertial confinement fusion (ICF), another deploys magnets and is called magnetic confinement fusion (MCF). Omar Hurricane and colleagues at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory opted for ICF with the help of 192 high-energy lasers at the National Ignition Facility in the US, which was designed specifically to boost fusion research.

A typical fusion reaction at the facility takes weeks of preparation. But the fusion reaction is completed in an instant (150 picoseconds, to be precise, which is less than a billionth of a second). In that moment, at the core of the reaction the pressure is 150 billion times atmospheric pressure. The density and temperature of the plasma created is nearly three times that at the centre of the sun.

The most critical part of the reaction, and one that had been a real concern for Hurricane’s team, is the shape of the fuel capsule. The capsule is made from a polymer and is about 2mm in diameter – about the size of a paper pinhead. On the inside it is coated with deuterium and tritium – isotopes of hydrogen – that are frozen to be in a solid state.

Hohlraum geometry with a capsule inside. Dr. Eddie Dewald/LLNL

This capsule is placed inside a gold cylinder, where the 192 lasers are fired. The lasers hit the gold container which emit X-rays, which heat the pellet and make it implode instantly, causing a fusion reaction. According to Debbie Callahan, a co-author of the study: “When the lasers are fired, the capsule is compressed 35 times. That is like compressing a basketball to the size of a pea.”

The compression produces immense pressure and temperature leading to a fusion reaction. Problems with the process were overcome last September, when, for the first time, Hurricane was able to produce more energy output from a fusion reaction than the fuel put into it. Since then he has been able to repeat the experiment.

Hurricane’s current output, although more than the hydrogen fuel put into the reaction, is still 100 times less than the total energy put into the system, most of which is in the form of lasers. Yet, this is a big achievement because reaching ignition just became easier.

Hurricane hasn’t yet reached the stated goal of the NIF that is to achieve “ignition”, where nuclear fusion generates as much energy as the lasers supply. At that point it would be possible to make a sustainable power plant based on the technology.

Scientists have been trying to tame fusion power for more than 50 years, but with little success. Although the National Ignition Facility, a US$3.5-billion operation, was built for classified government research, half of its laser time was devoted to fusion with an aim to accelerate research.

Zulfikar Najmudin, a plasma physicist at Imperial College London said: “These results will come as a huge relief to scientists at NIF, who were very sure they could have achieved this a few years ago.”

With laser-mediated ICF showing positive results, the obvious question is how does it compare with magnet-mediated fusion? According to Stephen Cowley, director of Culham Centre for Fusion Energy in Oxfordshire, “The different measures of success make it hard to compare NIF’s results with those of ‘magnetic confinement’ fusion devices.”

Culham works with magnetic confinement where, in 1997, the facility generated 16MW of power for 24MW put into the device. “We have waited 60 years to get close to controlled fusion. We are now close in both magnetic and inertial. The engineering milestone is when the whole plant produces more energy than it consumes,” Cowley said.

That may happen at the fusion reactor ITER, under construction in France, which is expected to be the first power plant that produces more energy than it consumes to sustain a fusion reaction.![]()

First published on The Conversation. Image credit: LLNL.