While the recently released low-cost rotavirus vaccine, Rotavac, is a great achievement for the country, it is not the “first indigenously developed vaccine”, as the prime minister’s office claims and then was parroted by newspapers. The honour goes to the bubonic plague vaccine developed in Bombay in 1897.

This is also not just a matter of semantics, where we ought to assume that the prime minister’s office implies “indigenous” to mean developed in Independent India. Because, as we have seen in the past, the prime minister is only too happy to (wrongly) claim centuries-old achievements to be “Indian innovations”.

India has played an important role in the history of vaccine’s use to fight disease. Their use means that the poorest of the poor today can live well beyond the age at which most kings died not too long ago. And the least we can do when we take vaccination forward in India today is to honour our past achievements.

Honouring history

The use of the first vaccine was pioneered by English scientist Edward Jenner in 1798. In the two centuries since, we have developed vaccines to fight 25 diseases. Fittingly, the disease against which the first vaccine was developed – smallpox – has been eradicated globally. The next disease on the list of diseases to be eradicated by the use vaccines could be polio.

But for nearly 100 years after the smallpox vaccine came in to use, the process of developing vaccines against other diseases remained difficult. This is because a vaccine then needed a naturally existing weak form of the disease. In the case of smallpox, that weak form was found in cowpox.

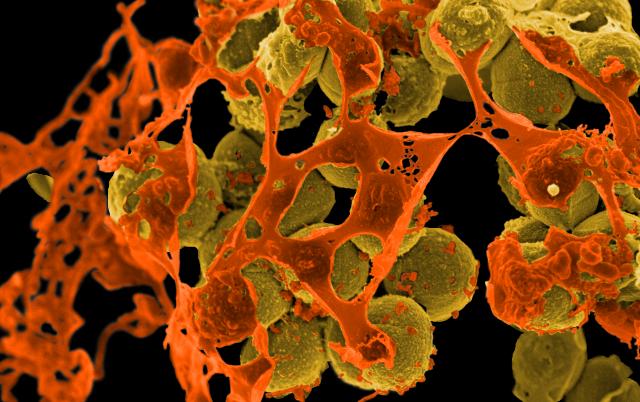

However, almost by accident, Louis Pasteur developed a laboratory method to generate a weak form of a disease. He used the method to create a vaccine against anthrax and chicken cholera. This is what revolutionised the work against infectious diseases.When injected into or ingested by the human body, vaccines work by stimulating the immune system and preparing it for when the real thing attacks in the future. Many vaccines provide lifelong immunity to a disease.

A young Russian, Waldemar Haffkine, was keenly following Pasteur’s work. At the time, cholera epidemics were common worldwide and someone had claimed to have isolated the bacteria that caused the disease. Despite Pasteur and Jenner’s work, many believed that that bacteria can’t be the sole cause behind cholera.

However, Haffkine agreed with the theory and worked hard on developing a cholera vaccine. He achieved success in 1892 and conducted the first human trial of the vaccine on himself. Having survived, he made the findings public but was dismissed by senior scientists.

The Plague Laboratory

Determined to see his invention have some impact on the world, he travelled to India where cholera epidemics had caused hundreds of thousands of deaths. His trials in Uttar Pradesh succeeded and he managed to vaccinate thousands. In 1895 he returned to France having caught malaria. But in 1896 was requested by the Governor of Bombay to help develop a vaccine against plague, which was ravaging the population of Bombay and Poona.

Against the advise of his French doctor, Haffkine travelled back to India and worked persistently to develop a plague vaccine. He succeeded within months, and, like the last time, tested the vaccine on himself. Within a few years, the vaccine was used to inoculate millions of people.

In 1899, a former residence of the Governor of Bombay was turned in to the Plague Laboratory and Haffkine made its director. The lab was renamed the Haffkine Institute in 1925, and remains an active institute for biological research in the country.

Haffkine was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1897. A London magazine wrote this about the announcement: “a Russian Jew, trained in the schools of European science, saves the lives of helpless Hindoos and Mohammedans and is decorated by the descendant of William the Conqueror and Alfred the Great.”

If you forgive the colonial tone, it is an apt eulogy in a rapidly globalising world that was being created then. His work is arguably no less “indigenous” to India than Rotavac, so it is sad that we forget such a legacy in celebrating the country’s new achievements.

First published in Lokmat Times. Image from Wikipedia.