A new hybrid explosive is safer to handle but still powerful

Modern warfare involves plenty of new technology, from pilotless drones to powerful computer networks and satellite sensors. But the explosives which are used in battle were invented a long time ago. The two most commonly deployed belong to a class of organic chemicals called nitramines. One, RDX, is also widely used in industrial applications like mining and demolishing buildings. Its use as an explosive began in the 1920s. HMX, a related compound and one of the most powerful explosives, dates back to the second world war. Both are sometimes used with trinitrotoluene, a different type of compound more commonly known as TNT. It is over 100 years old.

A good explosive needs to be extremely powerful but not too sensitive to avoid its being detonated accidentally, such as by dropping it. These can be conflicting properties. As Alex Contini of the Centre for Defence Chemistry at Cranfield University in Britain points out, explosives developed in recent years are either too sensitive or too expensive for large-scale use.

One such explosive is CL-20. This was developed by the American navy as a rocket propellant, a substance which involves the sudden release of energy by rapid oxidisation, in effect a controlled explosion. CL-20 is more powerful than RDX and HMX, but its higher sensitivity means that it also explodes more easily.

The most common way to desensitise an explosive is by mixing it with a non-explosive material, such as wax or paper. Although that works, it also reduces the amount of bang you get. What if the desensitising material is itself an explosive of lower sensitivity? The problem is that the resulting material is as sensitive as its most sensitive component.

Adam Matzger of the University of Michigan and his colleagues have discovered a way around that problem by using a process called co-crystallisation, which is commonly used by drugmakers to modify the physical properties of a pharmaceutical. They report in Crystal Growth & Design that by mixing CL-20 in such a way they have been able to lower its sensitivity but retain most of its explosive power.

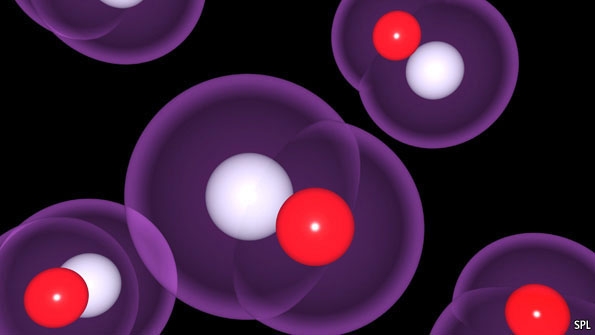

At the heart of the process is the formation of crystals, an ability endowed to some materials by nature. Crystals are the result of molecules arranging themselves in a regular pattern extending in all three dimensions. Sometimes two crystalline materials that do not react with each other can be mixed to form a so-called co-crystal. To do that they are both dissolved in a common solvent, then left alone to crystallise together. Because the arrangement of molecules within the co-crystal is very different from the original crystal, it modifies the physical properties of the material—in this case CL-20’s sensitivity.

Dr Matzger made a co-crystal consisting of two parts of CL-20 and one part HMX. The hybrid explosive has nearly the same explosive power as CL-20 but the lower sensitivity of HMX. Because the process of crystallisation can be scaled up relatively easily, Dr Matzger, whose work was funded by America’s Defence Threat Reduction Agency, thinks this new explosive could make a bigger bang soon.

First published in The Economist. Also available in audio here.

References:

- Matzger et al, Crystal Growth & Design, 2012

- Matzger et al, Angew Chem Int Ed, 2009

List of references here. Free image from stock.xchng.