Drug discovery is a long, arduous and expensive process. Is it worth it?

“One minute I was looking at death. The next, I was looking at my whole life in front of me,” said Suzan McNamara, a patient suffering from chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), a nasty form of blood cancer. She had just heard that she would be receiving doses of imatinib, a drug that had shown remarkable recovery among patients of this cancer. Four decades of research was needed to make this drug, and to enable such a moment for a cancer patient. It is Ms McNamara’s story and that of many others like her that could possibly justify billions of dollars and years of efforts put into discovering drugs.

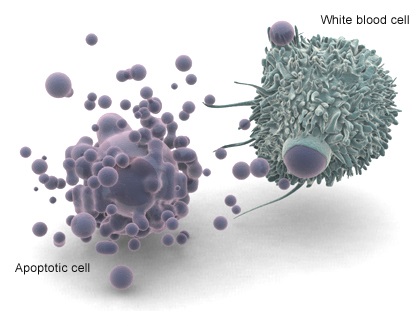

CML causes unregulated growth of white blood cells leading to pain, debilitating illness, and, before imatinib was discovered, all too often, death. The only options for treatment, before the drug therapy became common, were a bone marrow transplant, which is very risky, or daily infusions of interferon, an artificial way of boosting a patient’s immune system that has severe side-effects.

The process of discovering a drug like imatinib, commercially known as Gleevec, is a long one. First pharmacologists pick apart the workings of the disease and find a pathway that can be targeted. Then chemists design molecules or use readymade libraries of molecules to block (or, occasionally, activate) that pathway. Typically, of the 5000 molecules that showed promise at this first step, on average, only five are deemed safe enough to undergo human trials. Then, after three to six years of clinical testing, only one of those five molecules may become a drug. Finding a drug is literally like looking for a needle in a haystack. All considered, the success rate is 0.02% and it requires more than a decade worth of research at an average cost of $1 billion.

But imatinib was worth it. It was the first drug that could precisely target cancerous molecules. The science that underpins the achievement began with a discovery in 1960. Two researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that cancerous cells possessed a particularly small chromosome (number 22 out of the 23 chromosomes that make up human DNA), and this was proposed as the cause of unregulated growth. This was the first time that cancer was linked to a genetic abnormality.

How that abnormality led to cancer remained a mystery until new techniques to visualise segments of this chromosome were found in 1973. Then Janet Rowley, of the University of Chicago, showed that the small size of chromosome 22 was due to an exchange of one of its large segments with a small fragment from chromosome 9. The alien material on chromosome 22 now led to the production of a cancer-causing protein. This rogue protein, an enzyme, was involved in the regulation of cell growth. Dr Rowley postulated that blocking this enzyme should stop cancerous cells.

The charge to find the blocking agent was taken up by medicinal chemist Nicholas Lydon, of Novartis, and oncologist Brian Druker, then of the Dana-Faber Cancer Institute in Boston. They needed to find a molecule that will selectively block the rogue enzyme and leave hundreds of useful ones alone. Following the iterations of the drug discovery process, the team took eight years of efforts to find imatinib. In Phase II clinical trials nearly every patient who took the drug felt surprisingly better in a short period of time, which led to a fast-tracked approval for the molecule from the Food and Drug Administration in 2001.

Imatinib was also approved for treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumours and other forms of leukaemia, too. Earlier this year, Dr Rowley, Dr Lydon and Dr Druker received the prestigious $650,000 Japan Prize given for outstanding achievements that advance the frontiers of knowledge. “Their work shocked the world of clinical medicine”, the prize citation said. Times have changed drastically from early 20th century when patients depended on good fortune, as drugs were often only found serendipitously.

Ms McNamara was diagnosed with CML in 1998. By the time she received imatinib through a clinical trial in January 2000, her condition had become quite severe. “I was basically on my last limb,” she recalls. Before imatinib was discovered, only three out of five CML patients survived for more than five years after diagnosis. But a 2011 study showed that even eight years after diagnosis, only 1% of CML-related deaths occur among patients using the wonder drug.

With her health restored to normal, Ms McNamara went on to get a PhD in leukaemia research. Quite early in her studies she realised she may not be the one to cure leukaemia herself, but she said, “I might publish one paper that has one key for the next person to go a step further. That’s important”.

Drug discovery is a long, arduous, and expensive endeavour, but it is a process that is being continuously refined to produce results faster and more cheaply. Researchers consider themselves fortunate if they witness the successful launch of a drug in their lifetime, but extraordinary stories of patients motivate them to keep improving this process and searching for that elusive molecule.

Free image from here.