Developing new drugs is hard and expensive. The lengthy process from initial discovery to the market is some times compared to the difficulty of putting a person on the moon. Despite accusations that the pharma industry is evil, the real reason could be summarised pithily in what one scientist said: “Drugs are expensive because we are stupid.”

Even after studying some diseases for more than 100 years, we are not close to understanding them well enough. With so many unknown factors at play, the fact that we are able to still find relatively simple chemicals to effectively act as drugs is pretty amazing.

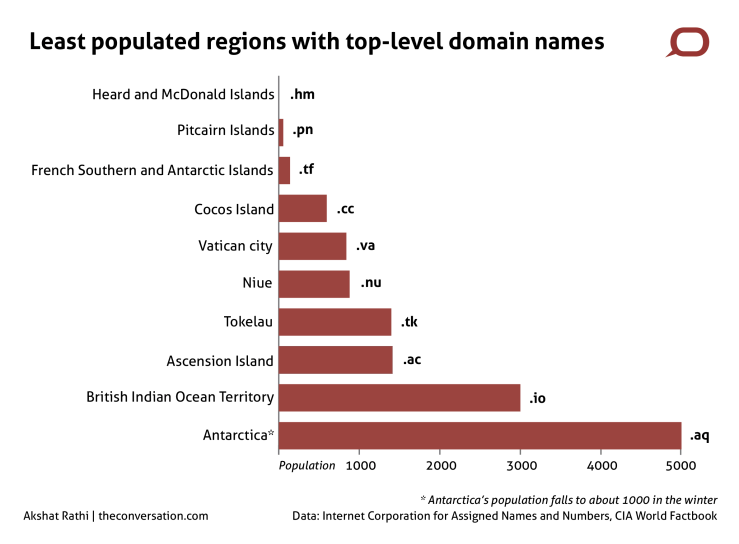

But with much initial success, the productivity of the pharma industry has been falling for many decades. According to John LaMattina, former president of global research and development at Pfizer, “30 is the new 50” in the drug industry. He is referring to the number of new drugs approved per year, which has been on average declining since the 1960s. This is happening at the same time as research and development (R&D) costs are going up.

Finding the true cost of a new drug is a complex and controversial exercise. However, one acceptable way to calculate it is to divide total R&D spend of pharma companies by the number of new drugs produced. Because of differences in agreeing what constitutes R&D spend, even this measure produces only a range – the cost of a new drug is somewhere between US$1 billion and US$5 billion.

However, many argue that simply looking at the rising costs does not give the true measure of the pharma industry’s productivity. New drugs don’t always mean effective new treatments. According to new studies just published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Efthimios Parasidis of Ohio State University writes on The Conversation that nearly half of the new drugs between 2005 and 2011 received an approval without the drug company needing to show that those drugs had any tangible benefit to a patient.

With rising costs and fewer new drugs, the pharma industry could do with a boost in the arm. That, however, seems to be a hard find.![]()

First published on The Conversation.